When Is Stress a Good Thing?

Apr 26, 2025

The information below is supported by the podcast above

The word stress tends to be judged only as a 'bad thing', but the fight-or-flight, adrenal response is neither good nor bad, it is simply a provocation to a reaction - yes, a fear-based reaction but also part of excitement, motivation and activity. You would not want to be without the protective effects of this immediate cascade of mind-body events as it allows you to act quickly in the moment. It is when we get caught in such heightened responses that the 'stress-related conditions' we associate with too much stress (with little come down or recovery time) can occur; eg sleepless nights, anxiety, overwhelm, IBS, headaches and even burnout.

The stress response is how we respond to challenges, real or perceived fears, change that requires immediate attention and raised attention when we are working out if something feels safe or unsafe. Stressors are those factors that provoke this response. We can't always control those stressors we're exposed to, but we can support recovery capacity and notice our need for quality time to build resources back up. We can also notice that much stress for humans is psycho-social - different to the more wild, physical stressors our ancestors would have faced - our concerns are often around expectations, information overwhelm and choices.

The biology of stress

At its core, stress is a survival mechanism. Our fight-or-flight response evolved to help us escape danger: a rush of adrenaline, increased focus and faster heart rate are all designed to get us out of harm’s way. Our stress response is still acting as if we were in the wild - mounting a full-blown physical response - when the nature of the modern world is more often more societal, security based around money and internal rumination. Even if we are sitting still and worrying about paying the gas bill, our biology is readying us to stand our ground and fight or run away. When we don't get to follow through with physical activity we can be left with tense muscles and raised blood pressure that can get stuck.

As described in my book The De-Stress Effect, you may be experienced an overload of stress if you:

As described in my book The De-Stress Effect, you may be experienced an overload of stress if you:

- React to situations or events in a more dramatic or heightened way than you afterwards think you should have?

- Feel overwhelmed if a task or demand you didn’t expect occurs suddenly?

- Feel demotivated, as if every chore is a bigger mountain than it was, say, a year ago?

- Feel compelled to take on more and more, even if you don’t think you can handle it?

- Feel angry, scared, anxious or irritable – or swing from one to another?

- Tend to take things on for others, regardless of your time limits and feelings?

- Feel the need to ‘just keep going’ or to juggle all your balls in the air?

- Avoid relaxing and letting go more and more?

- Avoid difficult situations, people or crowds – even if you know, deep down, you might enjoy them?

- Seek out exciting, high-risk situations, exercise or hobbies?

But this powerful system isn’t only reactive to threats; it is our nervous system moving into active mode - it can also be triggered by things that need getting going, are fascinating or need a quick reaction. For instance public speaking, job interviews, or the excitement of a new project. In these contexts, stress serves as a motivating force. It sharpens our senses and readies us for performance. However, this kind of stress is meant to be short-lived and we’re designed to rest and recuperate afterward.

Without rest, even the motivating energy of the stress response can become depleting. This is the tipping point where what helps us achieve and adapt starts to wear us down.

Some forms of stress however, when experienced in the right dose and with the right recovery, can actually support health, build resilience, and help us thrive. Here we explore the difference between harmful stress and its healthier counterpart, eustress, the kind of challenge that stimulates growth, not collapse.

Eustress: the power of supportive challenge

Eustress is the kind of stress that’s invigorating and challenges our body systems to adapt to change; a process called hormesis. It’s the pressure that comes before an exam or performance or generally something challenging, but is ultimately within our control. These kinds of experiences stretch us in the ways that keep us engaged with life, support cycles of sustained energy and full rest, and sleep.

Characteristics of positive stress include:

-

A clear end point - we know it won’t last forever.

-

An element of choice or control - we can prepare and respond.

-

A sense of progress - we can see small achievements along the way.

-

Time to recover - periods of rest allow integration and avoid burnout.

Examples of this type of stress include training for a race, studying for an exam, or giving a talk. Even everyday things like managing a full day of parenting or navigating a difficult conversation can offer opportunities for growth, as long as they’re followed by rest and reflection. We can handle sudden and unexpected bouts of stress, when we have the space to step away and reflect; it's relentless, constant and oversubscribed ways of living that leave us feeling there is little escape and with few resources available to cope.

Gentle stressors: supporting the body and mind

Gentle stressors: supporting the body and mind

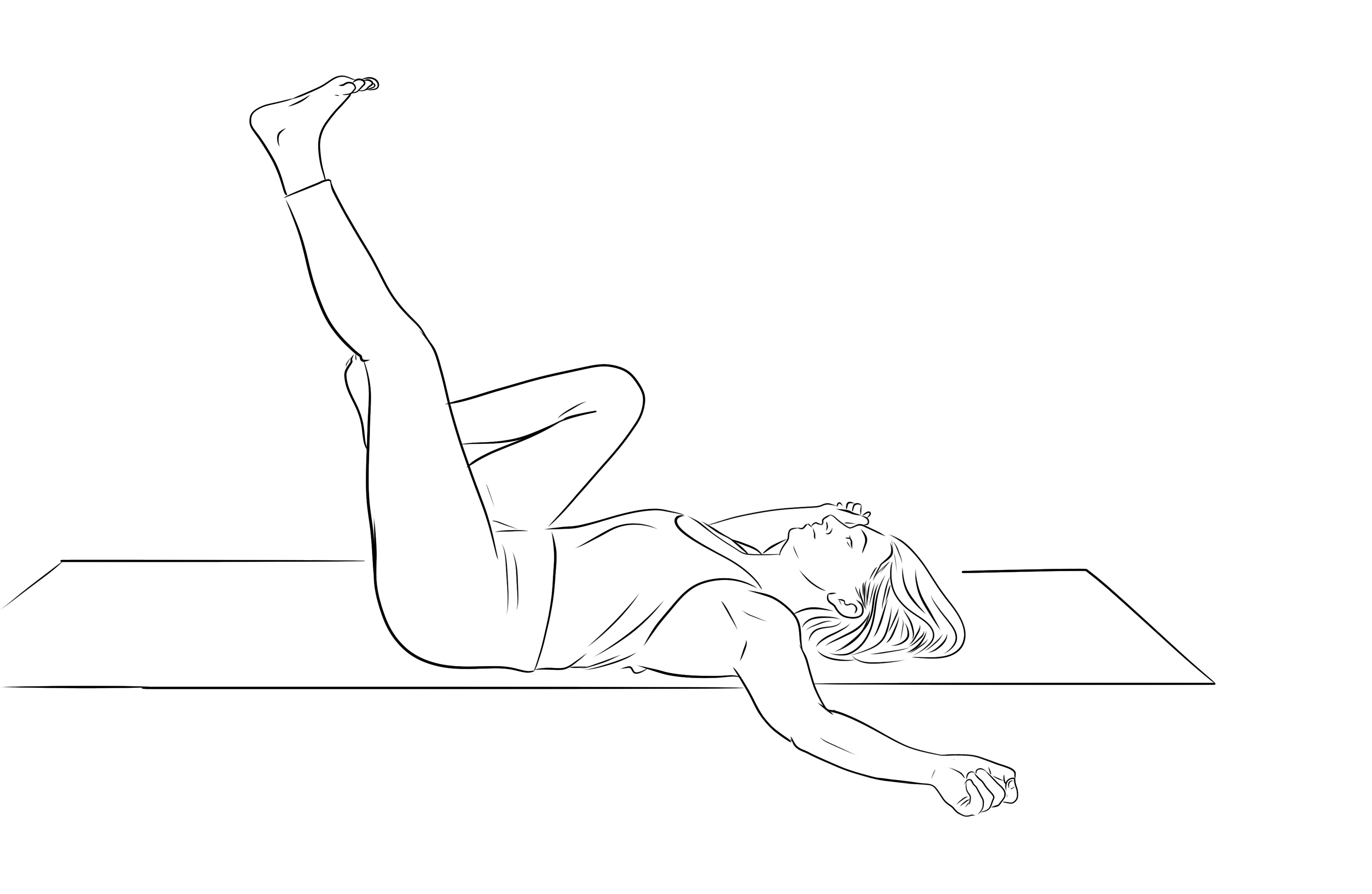

Mild stress, regularly applied, is how the body gets stronger - these prompt the adaptive capacity of hormesis that ultimately leads to resilience.

One of the most well-known actions of eustress that promotes the adaptation is weight-bearing exercise increases bone density - bone needs to feel the stress of muscle pulling on it to prompt the signal for the cells that build up bone (osteoblasts) to come into action. Exposure to cold, like finishing a shower with a blast of cool water, stimulates the metabolism and immune system. Navigating hunger between meals supports metabolic flexibility and mirrors the natural patterns of intermittent fasting found in wild animals.

Even holding a challenging yoga pose teaches us how to stay calm under pressure and acts as direct training for emotional regulation - this illustrates how yoga is not something we 'do' (purely physical) but a state of union (yoga means 'to yoke') that allows us to examine our habits (samskaras) and find space around life's emotional and mental challenges through a relationship with difficulty met with compassion within practice.

These kinds of stressors can be thought of as microdoses of challenge. They gently stretch our limits and help us adapt over time, ultimately making us more resilient to the larger stresses life inevitably brings. Resilience is not a hardening or armouring, but rather the ability to bend, reroute and stay flexible to options - like a tree bending in the wind.

The danger of chronic stress

Negative stress is different - this is the kind that lingers. It comes from ongoing situations that feel outside our control like work we can’t escape from; financial worry, unresolved trauma, or even the constant inner voice of self-judgment.

These stressors don’t end and they don’t offer recovery. They keep the body in a constant state of alert, often referred to as “living on your adrenals.” Over time, this can result in chronic inflammation, exhaustion, and a range of health issues.

The problem isn’t stress itself, it’s when stress becomes chronic, and our system doesn’t get the signal that we’re safe again and can come down to rest and recovery states that spare energy and allow healing of tissues and immune regulation.

More from The De-Stress Effect:

"Our culture places so much emphasis on external factors, from gauging health by outside appearance to comparing ourselves to the bendy student on the next yoga mat. This outside focus clouds the real truth: that all of those projections are subjective and deciding our world view on how attractive/thin/successful/popular we perceive ourselves to be at any given time limits us and can’t make us happy.

Moving inwards to how we feel – and listening to our bodies rather than the constant barrage of thoughts – is the way to contentment. Even if the answer to the question ‘How do I feel?’ isn’t always ‘Great!’, this is the essence of mindfulness. Self-care, diet and lifestyle changes can help you feel the best you can be – and to feel more acceptance when that’s not so good.

This is the optimal starting place to recognize and explore the most effective strategies for you to escape from stress and sensory overload, or just to gather in to a place of perspective whenever you need to. With chronic stress or trauma, our ability to feel can often become numbed - mindful and somatic practices are designed to help us connect back to feeling."

Regulating the stress system

So how do we invite more eustress and reduce the damage of chronic stress?

The answer lies in how we care for ourselves. By prioritising rest, presence, and nourishment, we create a buffer for our nervous system that can meet challenges without collapsing under them.

Some practices that help regulate stress:

Some practices that help regulate stress:

-

Mindful movement such as yoga or Qi Gong, which help us stay aware and grounded.

-

Meditation and breathwork, which calm the nervous system and bring us back to the present.

-

Spending time with loved ones, especially those who make us feel safe, heard, and happy.

-

Nourishing food and self-kindness, treating ourselves with the care we’d offer a dear friend.

These are not luxuries - they’re essential. They allow us to return to a balanced state and cultivate the adaptive qualities that stress, when well-managed, can bring.

Reframing stress

We may never eliminate stress - we can navigate our lives to allow more space, recovery and self-care, but things inevitably come along to upset and overwhelm us. That is the nature of life - it not what happens to us, but our responses to those that define how the quality of how we live. Trying to rid ourselves of it completely can feel impossible and defeating. Instead, we can start to see stress as useful information - something to relate to, rather than fear.

By embracing the right kinds of challenge and giving ourselves the care we need in response, stress becomes not something to avoid, but something that can shape us, strengthen us, and carry us forward.

Following this theme I invite you to explore my online course Yoga for Burn-Out and Fatigue Conditions (including post viral fatigue and Long-Covid)

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our community to receive the latest news and updates from Somatic Therapeutic Yoga Training Limited. When you sign up, you'll also receive access to our Yoga Teacher Community and receive two ebook samples of my recent Yoga Teacher training books.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.